Preview

Description

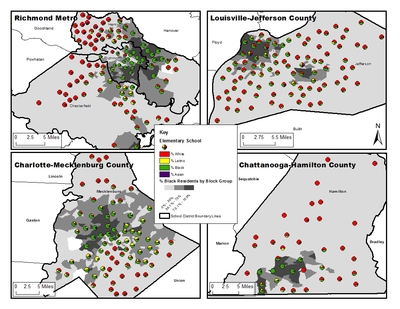

From the late 1990s to 2010, the Richmond and Chattanooga areas continued to report elementary school enrollments that largely mirrored the racial makeup of nearby neighborhoods. In other words, school segregation overlapped very closely with housing segregation. As Richmond’s separate suburban school systems became more diverse, so too did their school enrollments. Increasingly, the predominant pattern of minority segregation in urban schools and neighborhoods extended to parts of the suburbs just over the city-county boundary line. The same trends were evident in Chattanooga-Hamilton County, indicating again that limited school desegregation policy implemented after the 1997 merger did not confront the school-housing relationship as effectively as the controlled choice policies in Louisville and pre-unitary Charlotte (see Maps 7 and 8).

Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s success in disrupting the relationship between school and housing segregation eventually succumbed to mounting political and legal opposition to school desegregation. By 2000, schools in and around Charlotte’s urban core, particularly in the western and northwestern quadrants of the city, were beginning to reflect the overwhelmingly black populations of surrounding neighborhoods. Ten years later, Map 8 shows that Charlotte-Mecklenburg school enrollments very much mirrored neighborhood segregation—not necessarily surprising given the post-unitary status emphasis on neighborhood schools. The earlier disconnect between patterns of residential and school segregation had all but disappeared.

With these developments unfolding in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Louisville-Jefferson County became the only metro under study to consistently disrupt the relationship between black-white school and housing segregation. Maps 6–8 display the impact of the metro’s ongoing commitment to a comprehensive city-suburban school desegregation policy. Schools across the city-suburban landscape reported roughly even shares of black and white students, reflecting the guidelines in the controlled choice policy. Still, by 2009 several elementary schools in Louisville’s still highly segregated inner city had become predominantly black and Latino. This may have been related to the struggle to craft and implement a revised student assignment plan to comply with the 2007 Supreme Court decision in Parents Involved.

Source: NCES Common Core of Data, 1992–93, 1999–2000, and 2009–10.

Creation Date

2016

Is Part Of

VCU Mapping Files to Accompany When the Fences Come Down: Twenty-First-Century Lessons from Metropolitan School Desegregation

Rights

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Date of Submission

March 2016